Hockey Stick growth and Github Stars

Common open source software (OSS) / venture capital (VC) metrics are flawed. This surprises no one; metrics are hard.

Since starting a company around a pre-existing community OSS project, Dask, I’ve had many conversations on this topic. I’d like to share two prototypical conversations that show the need for nuance below. One about hockey stick growth, and the other about GitHub stars.

Startup Founder asks about Hockey Stick Growth

Another startup founder wanted to drive adoption to his product by creating an open source project that quickly took off and was curious about how to rapidly get project-market fit.

-

SF: Dask seems really successful. How did you quickly get traction with the open source community?

Me: We didn’t. Dask is the result of six years of listening and diligent community service.

The full community-based OSS timeline doesn’t make make sense for a for-profit company.

He went on to ask about rapid, hockey-stick growth.

-

SF: Well, along that journey, what happened that cause you go finally achieve hockey-stick growth?

(Image source,

Forbes)

(Image source,

Forbes)Me: Never.

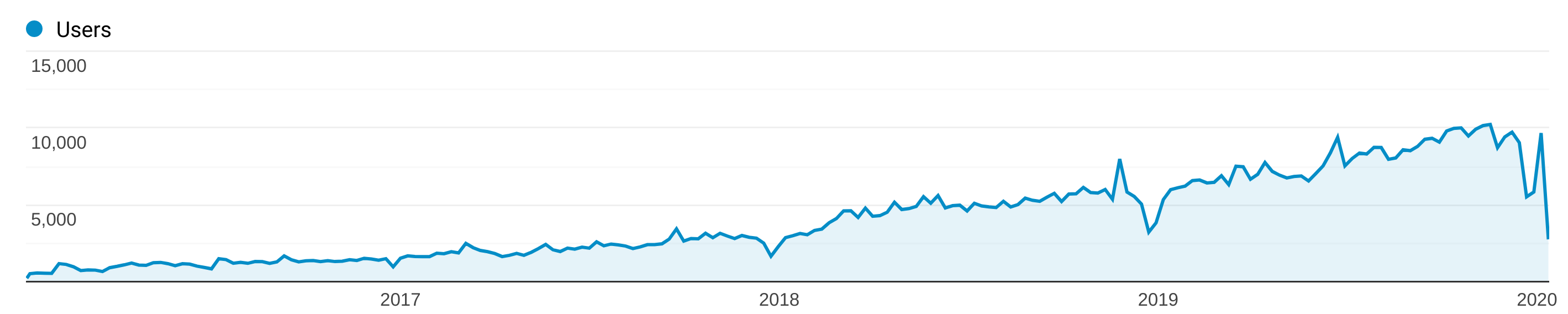

Dask grew organically. See my post on Estimating Users and our weekly unique IPs to API documentation (my preferred metric)

I usually call this growth curve “organic growth” or “natural growth”, which I think reflects a far more stable community of users with deep understanding between the user and developer communities.

We need to find a way to make organic growth cool again. Rather than Hockey-stick growth we can call this Scimitar growth? :)

Venture Capitalist asks about Github Stars

In another conversation a VC investor trying to evaluate Dask’s popularity asks about GitHub stars.

-

VC: So how popular is Dask? How many GitHub stars do you have?

Me: It’s hard to count, as an ecosystem project Dask affects dozens of other projects.

We also don’t spend our time trying to collect stars

-

VC: Yeah, but how many stars?

Me: Sigh, maybe 7k in the main repo, 2k each in a few sub-repos, and then another 5k each across various sister projects like RAPIDS, Prefect, Xarray, …?

-

VC: I guess that’s ok

Me: But a better metric is probably that 5% of Python users use Dask (according to the PSF survey, which is biased towards people who care).

So any company that has 20 Python users has a decent chance of using Dask internally. Apache Spark is 2-3x higher, Apache Hadoop slightly higher, and Apache Hive slightly less, Apache Beam about 5x less.

Dask is by far the most popular non-JVM parallel computing framework in Python ever made.

-

VC: Oh.

I don’t know a better metric than GitHub stars that one can get immediately on the open internet. I don’t envy investors. Rapidly assessing the commercial potential of highly technical software is hard. It’s rare to find individuals with dual expertise in distributed systems and business acumen.

Still, the star metric makes me less-than-happy. It’s a measure of hype, not of use, or of utility.

Thoughts

In the specific case of Dask, hockey stick growth among users is no longer possible. We’ve reached user penetration that’s already pretty high (the 5% number is for all Python users, including web developers, and people who will never touch big data). The thing to think about now is company adoption. Just because some data scientist is using Dask inside of every Fortune 50 company doesn’t mean that those companies use Dask throughout. That metric is harder though.

Regarding stars, most of the excitement around Dask today is indirect. It’s for sister projects like RAPIDS, Prefect, Pangeo/Xarray, XGBoost, and so on that Dask supports. As a community project, Dask tries hard to blend in and support peer projects. This integration is the strength of community software. Dask and many other OSS projects strengthen the collective weave of PyData. We’re less like a monolith, and more like carbon fiber. Hat tip to similar computational projects Arrow, RAPIDS, Numba, and Numpy all of whom work tirelessly on standards and open integration.

I fundamentally believe that pragmatic sustainable software is better built organically and collectively. I am curious what metrics might capture these more community-supportive behaviors.

blog comments powered by Disqus