Tips for Interactive HPC

This is co-released with a companion post Five reeasons to keep your HPC center, and avoid the cloud.

Scientific institutions today are considering how to balance their current HPC infrastructure with a possible transition to commercial cloud.

This transition is largely motivated by data science users, who find a mismatch between interactive workflows and HPC policies. These data science workloads differ in a few ways from traditional HPC. In particular they are data centric, interactive, and ad-hoc, using tools like Python and Jupyter notebooks rather than highly tuned C++/MPI code that runs overnight.

This mismatch causes frustration both for users and for system administrators. This frustration is reasonable. HPC hardware and policies weren’t designed for these use cases, and the rise of data science happened more quickly than our typical HPC procurement cycle. Fortunately, there are steps we can take to adapt existing HPC centers for data science use today. These steps can either be taken at the user level (this is prevalent today) or at the institutional level (this is generally rare, but growing quickly).

This post briefly outlines three of the main causes of frustration:

- Rapidly changing software environments

- Accessibility and rich user interfaces

- Elastic and on-demand computing

This post also describes technology choices that users and institutions make today to solve or at least reduce this frustration. In particular, we focus on tools common in the Python ecosystem, including Conda, Jupyter{Hub/Lab}, and a marriage of Dask and job schedulers. This post can be seen either as a how-to for users, or as a sales pitch to IT.

Software environments

Historically, when a user needed some piece of software, they would raise a ticket with the HPC system administrators who would then build the software and include it as a module. This might take a few days.

Today, modern data science users can change their software stack several times a day, and rely on a variety of both stable and bleeding edge software. Additionally, every data science user uses a slightly different set of libraries, compounding this problem by 100x (assuming an HPC center supports only 100 users).

Asking an IT system administrator to manage hundreds of bespoke software environments is infeasible. Neither side would be happy with the arrangement.

To solve this …

-

Users today often install their software stack in user space, commonly with tools like Anaconda or Miniconda, which were designed to be self contained and require only user-level permissions. For many fields, Anaconda today includes most libraries that a data scientist needs, including both high-level Python and R libraries, as well as native compiled libraries like HDF5, MPI, and GDAL. They might not be optimally compiled for the machine at hand, but they’re often good enough.

-

System Administrators understandably have mixed feelings about this. It is both liberating and scary to give up control over the software that runs on your machine. In the end though, at least now it’s the user’s responsibility to take charge of their own problems, freeing up IT for other more institutionally focused work.

Easy Access and Rich User Environments

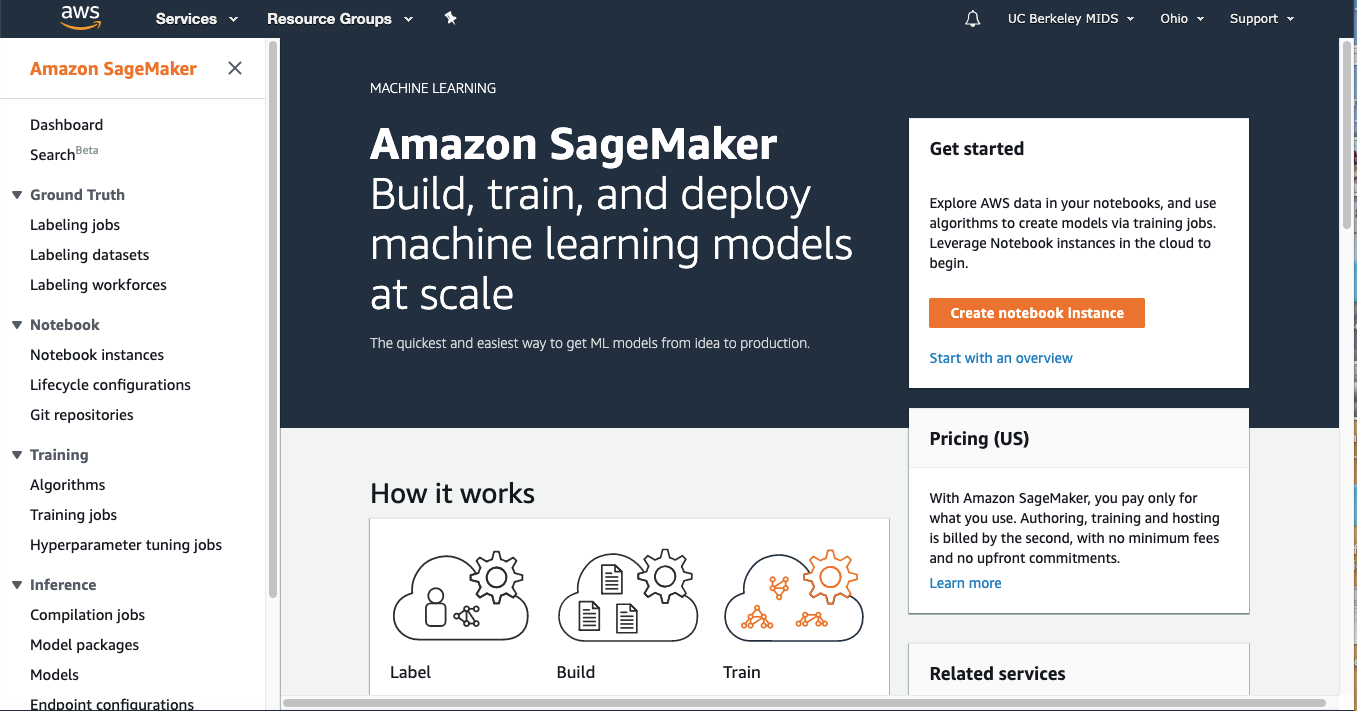

Most cloud offerings today provide slick visual user interfaces with Jupyter notebooks, dashboards, point-and-click UI’s and simple authentication that appeal to less technical data science or science audiences.

In contrast, users on HPC machines typically open up a terminal window, SSH in a few times (checking their security token each time), and operate in bash. This experience feels clunky and uninviting to newer users who may not have CS backgrounds.

To solve this …

-

Users today often use SSH-tunneling to get a rich environment like JupyterLab up and running, and from there they use Jupyter notebooks, install various dashboards, open up a variety of Terminals (who needs

tmuxanymore?).Here are some images of such a session.

-

System Administrators might support this kind of activity by deploying JupyterHub within their institution. JupyterHub integrates nicely into existing job queuing systems like SLURM/PBS/LSF/SGE/… and can use the existing security policies that you already have in place, including two-factor security tokens.

This gives users the visual rich UI/UX that they’ve come to expect, while still giving system administrators the security and control that they need in order to maintain stability over the system. It also, conveniently, gets users off of the login nodes and onto compute nodes where they belong.

Several large and well respected supercomputing centers have deployed JupyterHub internally, including NERSC, SDSC, NCAR, and many others.

For more information, interested readers may want to watch this talk from Anderson Banirhiwe at SciPy 2019 on using JupyterHub from within their supercomputing center.

Elastic scaling and On-demand computing

Data scientist’s workloads are both bursty, and intolerant to delays.

Often they want to quickly spin up 50 machines to churn through 100 TB of data for five minutes, generate a plot, and then stare at that plot for an hour. Then, when they get an idea, they want to do that again, immediately. They’re comfortable waiting for a minute or two, but if there is an hour-long wait in the queue then they’re going to switch off to something else, and they’re probably not going to try this workflow again in the future.

These bursty workloads don’t fit into most HPC job scheduling policies. These policies are designed to optimize not for on-demand computing, but for high utilization and batch jobs. This policy causes some users a great deal of pain because it means long wait times even for very short jobs.

Today there are a few solutions to this, but they’re not perfect without some help from IT.

-

Users end up doing one of the following:

- Download a sample of the dataset locally and abandon their HPC resources

- Keep their 50 machines running the entire time, wasting valuable resources

- Get frustrated, and buy some AWS credits

That is, unless of course there are some gaps in the schedule, and if IT have taken some steps to promote small jobs.

Most HPC machines don’t hit 100% utilization. There are always little gaps in the schedule which, if your jobs are fast and loosely coupled, you can sneak into. A good analogy I’ve heard before is that if you fill a bucket full of rocks, you can still pour in a fair amount of sand. Our goal is to be like sand.

Data science oriented distributed systems like Dask, are designed to work with job-queue schedulers (PBS/SLURM/SGE/LSF/…) to submit many small fast jobs and assemble those jobs into a broader distributed computing network. Users frequently use systems like Dask to take over 10-20 nodes and process 100 TB datasets today. It’s commonly run on a large number of supercomputer centers.

For more on this, see Dask Jobqueue

-

System administrators can improve the situation here by making a few small policy decisions:

- Promote very short jobs to the front of the queue. This is a common option in many HPC job queuing systems.

-

Consider creating and advertising high priority queues that are designed for bursty workloads. Users are comfortable paying a premium for on-demand access, especially if it allows them to be efficient with their use of jobs (remember that their alternative is to keep their jobs running all the time, even when they’re staring at plots).

Many HPC systems are judged on utilization, but it’s important to remember that scientific productivity does not necessarily follow utilization perfectly. Policies that optimize slightly away from utilization may be better at producing actual science.

Summary

Our ability to generate large scientific datasets on supercomputers has vastly outstripped our ability to analyze them. It’s correct for us to drastically rethink how we support scalable data science workloads on these datasets.

However, in the meantime, we can use our existing infrastructure to great effect. Advanced users do this today and generate excellent science as a result. We should work to make these workflows more accessible to less advanced users, both by documenting best practices and by codifying some of these approaches into our software.

At the same time, we should also approach this from the systems administration side. Sysadmins want to provide systems that guide data science users towards safe and controlled behavior, while also giving them the tools they need to do great science.

Fortunately, new tooling is out there that was intentionally designed to bridge this IT-User gap, including Conda, JupyterHub, and Dask.

Thanks to Anderson Banihirwe, Jacob Tomlinson, and Joe Hamman for their review and help in writing this post

blog comments powered by Disqus